A plethora of asteroids in TESS data

Astronomy Asteroids Asteroid Physical Properties TESS

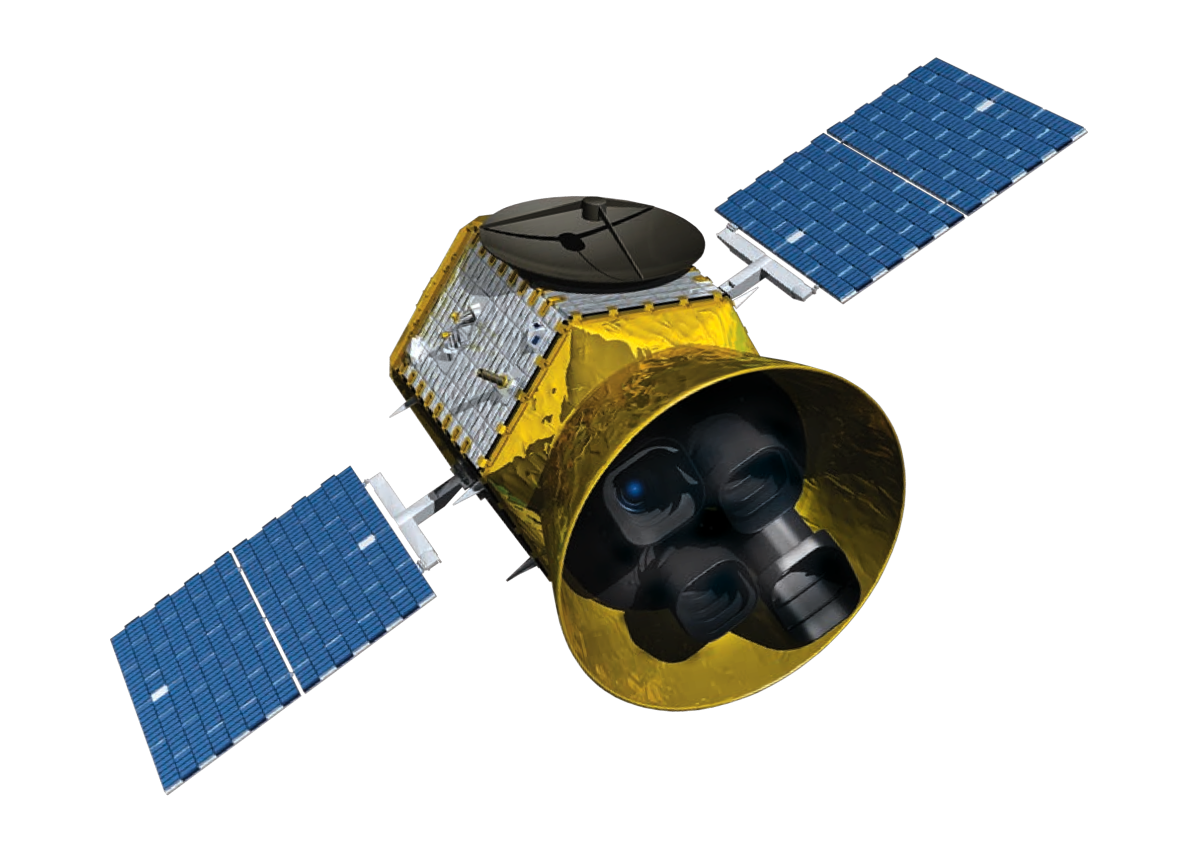

TESS is the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which was launched into space by NASA in 2018 to identify faint brightness variations in stars that are characteristic of planets orbiting around and transiting in front of these stars.

Over the course of its nominal two-year mission, TESS will monitor more than 200,000 stars with the photometric accuracy necessary to identify exoplanet transits. In order to observe this huge number of stars, TESS points at different “Sectors” in the sky, amounting to a total of 85% of the entire sky. Each Sector spanning 24° x 96° is observed over a period of about one month.

TESS data are publicly available through MAST - including calibrated Full Frame Images that are stacked over a period of 30 min each. Given the huge field of view of the TESS cameras, there should be an enormous number of asteroids in each frame at any given time. So I went out for an asteroid fishing expedition…

Extracting asteroids from TESS data

The idea is conceptually simple:

- download and pre-process the TESS Full Frame images for further analysis ;

- perform a background subtraction to remove stars and other fixed sources to improve the detection of moving objects;

- predict the locations of all known ~800,000 asteroids for the time of the observations in order to be able to identify them in the frames;

- perform photometry and measure their brightness.

Putting all these parts together, we can measure brightness variations of a large number of asteroids over a baseline of up to nearly one month - this is a unique data set that enables the accurate measurement of rotational periods over a continuous period of time that is not accessible from the ground: keep in mind that ground-based observations are restricted to night-time observations only, whereas TESS is able to observe 24/7.

This project is mainly a computational problem: running one out of four cameras per Sector on a desktop machine takes about one day. Multithreading has been implemented where possible to expedite the processing.

First results

A first cool result is shown in this short video clip:

This video shows the rotational lightcurve of asteroid 1693 Hertzsprung. The left plot shows a thumbnail image centered on the asteroid and the right plot shows the brightness of the target. As time progresses, the variation in brightness, which is caused by the asteroid’s irregular shape and rotation, becomes obvious. This specific asteroid has a rotational period of about 9 hrs. Gaps appear in the lightcurve when the asteroid comes too close to areas affected by image artifacts, which are highlighted with red overlays in the left plot.

Current status

The analysis of the complete TESS data set is now funded through a NASA grant and our first publication is available: McNeill et al. (2019)

And paper two is currently underway…

Resources

- McNeill, A., Mommert, M., Trilling, D. E., Llama, J., & Skiff, B. (2019), “Asteroid Photometry from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite: A Pilot Study”, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 245, 29., publication, arxiv