Are there Limits on the Applicability of Asteroid Thermal Models for Near-Earth Asteroids?

Astronomy Asteroid Thermal Modeling Asteroid Thermophysical Modeling

The vast majority of all asteroid diameters and albedos that are currently available have been derived from thermal infrared observations using a method called thermal modeling. Thermal models simulate the surface temperature distribution on an asteroid which is used to derive the thermal infrared flux that is emitted by the body. By varying the model parameters - mainly its diameter and albedo - the properties of an asteroid can be fit to observations of the thermal emission and hence estimated.

Thermal models are much simpler than the more sophisticated thermophysical models. For instance, they assume a spherical shape of the asteroid and the surface temperature is derived by assuming an instantaneous thermal equilibrium. Model definitions can vary. The Standard Thermal Model (STM) does not account for solar phase angle and assumes a very slow rotation and/or low thermal inertia of the asteroid, whereas the Fast-Rotating Model (FRM) assumes a fast rotation and/or high thermal inertia. The currently most widely spread model is the Near-Earth Asteroid Thermal Model (NEATM), which is based on the STM, but geometrically accounts for the solar phase angle and uses the so-called beaming parameter to modulate the surface temperature globally.

The NEATM is usually a good choice and applies to a wide range of atmosphereless bodies. However, theoretically there might be cases in which the FRM provides better estimates for the properties of an asteroid, namely for extremely fast rotating asteroids, asteroids with specific spin configurations, or under specific observing conditions. This work explores whether there are cases in which the FRM is superior to the NEATM in the case of Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs).

In order to investigate the performance of the NEATM and the FRM on NEAs, we simulate thermal-infrared flux densities using a more complex thermophysical model for 1 million synthetic asteroids and apply both thermal models to each of these datasets. The performances are compared using two custom metrics and marginalized plots for the simulation input parameters.

What we found is that in the vast majority of cases, the NEATM is clearly superior to the FRM - meaning that it derives better estimates of the targets’ diameters and albedos. Interestingly, the targets’ physical properties only have a negligible impact on the performance of both models, including the spin rate (even for rotational period of only a few seconds), high thermal inertias, and spin obliquities that produce surface temperature distributions similar to that assumed by the FRM.

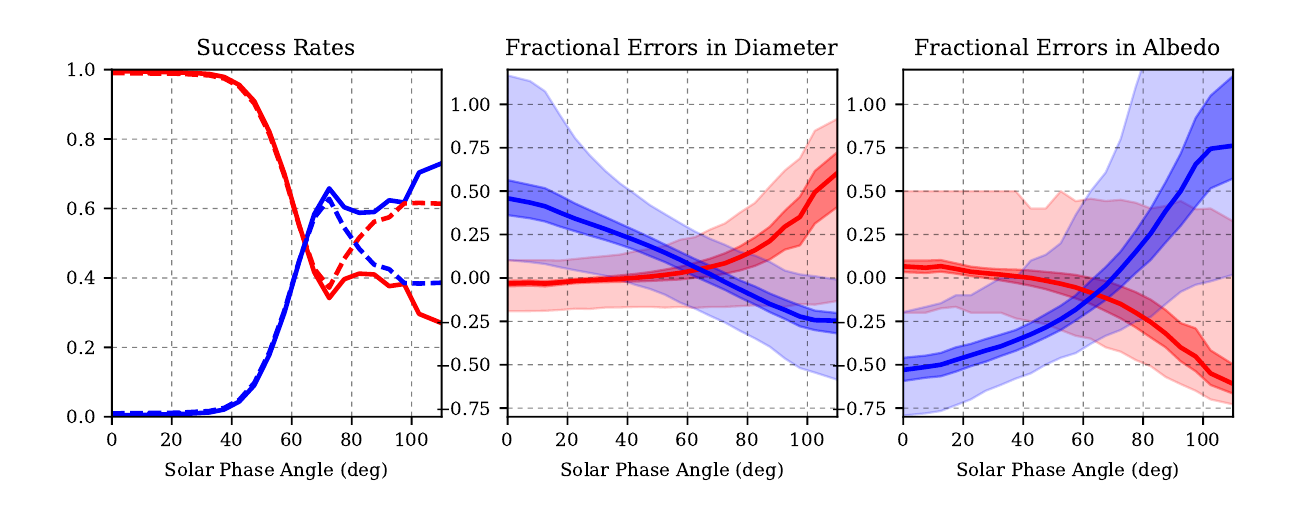

The most important result from this study is shown in the plot above (Figure 4 in the paper): we find that for solar phase angles greater than ~65 degrees, the FRM seems to perform on average better than the NEATM. It has been known before that the NEATM fails at high phase angles, but our study suggests an alternative to the NEATM for such cases.

We furthermore find that about 5% of all NEA diameters and albedos that were derived with the NEATM from Spitzer and WISE data are affected by this effect and are hence unreliable. Finally, we provide an empirical correction for diameters and albedos derived with the NEATM and the FRM as a function of solar phase angle.

Resources

- Mommert, M., Jedicke, R., & Trilling, D. E. (2018), “An Investigation of the Ranges of Validity of Asteroid Thermal Models for Near-Earth Asteroid Observations”, The Astronomical Journal, 155, 74., publication, arxiv